|

|

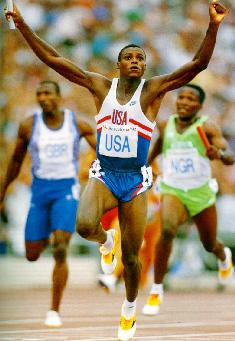

CLICK ON THE PICTURE TO GO TO www.carllewis.com

King Carl had long, golden reign

(Source : http://espn.go.com)

By Larry Schwartz

Special to ESPN.com

Carl Lewis has always amazed us. By distinguishing himself in two seemingly simple actions -- jumping and running -- for the longest time, he became unlike any competitor. With his unsurpassed talent in the long jump and his speed in the sprints, he has gone places where no other track and field athlete has ever visited.

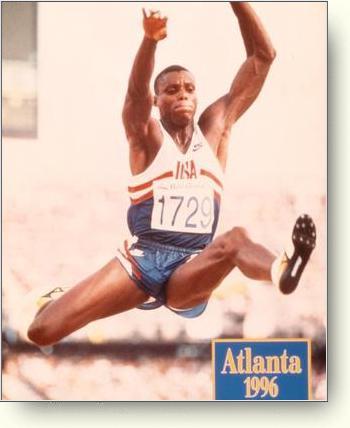

Carl Lewis capped his remarkable Olympics career by winning gold in the long jump at Atlanta in 1996.

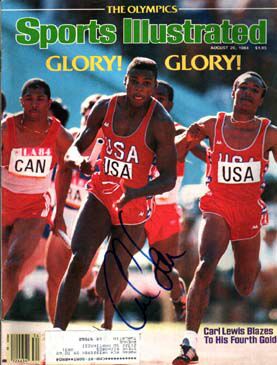

He didn't lose in the long jump for a decade, winning 65 consecutive competitions. He won four gold medals at the 1984 Olympics, equaling the 1936 accomplishment of his hero, Jesse Owens. He sped to a world record in the 100 meters. And then, when it appeared to be time for him to leave the jumping to younger athletes, he fooled us.

"You try to give a man a gold watch, and he steals your gold medal instead. You ask him to pass the torch, and he sets your Olympics on fire," Sports Illustrated's Rick Reilly wrote about Lewis, at the age of 35, winning his fourth consecutive Olympic long jump in 1996.

That unexpected and stunning victory gave Lewis his ninth Olympic gold medal, tying him for the largest gold collection with U.S. swimmer Mark Spitz, Finnish long-distance runner Paavo Nurmi and Soviet gymnast Larysa Latynina.

Yet, through all his triumphs, Lewis never came to be embraced by the country. He never became his sport's ambassador, his sport's Magic Johnson. He came across as haughty and arrogant, cold and calculating, aloof and abrasive. We like our heroes to display at least a minimum of modesty (see Michael Jordan), though it is not necessary to have the unpretentiousness of a Lou Gehrig.

The quest for perfection in most athletes is seen as a positive. In Lewis, it came across as a negative. "He rubs it in too much," said Edwin Moses, two-time Olympic gold medalist in the 400 hurdles. "A little humility is in order. That's what Carl lacks."

That lack of humility never made up for Lewis being handsome and articulate, of having stayed clean in a dirty sport, of being a crusader against steroid use. Lewis, like Frank Sinatra, did it his way. But unlike Sinatra, he didn't have the charm to go with the talent.

ZONE POLL

"Lewis' liberating cool liberates him, not necessarily us," wrote Sports Illustrated's Kenny Moore. "We might understand him best as forged by the 100, holding on to his solitude until the pack falls away."

Frederick Carlton Lewis was born July 1, 1961, in Birmingham, Ala., and raised in Willingboro, N.J., a suburban, middle-class, racially mixed environment. Bill and Evelyn Lewis raised Carl and his three siblings with the premise that they didn't have to bend to authority just because it's authority. "We don't like outside influence," said Carl's older brother Cleve, "and we don't like control."

Carl was seven when Bob Beamon set the remarkable record - 29 feet, 2 inches at the 1968 Olympics -- that would possess Lewis for his career. He competed in track on the town club his parents coached. When he was 10, he and a cousin had their picture taken with Owens, who advised him to have fun.

Small for his age (his younger sister Carol called him "Shorty") and shy, Lewis sprouted so suddenly at 15 (2 inches in a month) that he had to walk with crutches for three weeks while his body adjusted. As a high school senior, his 26-8 leap broke the national prep long-jump record.

Lewis went to the University of Houston, instead of local track power Villanova, to become more independent. By 1981 he was No. 1 in the world in the 100 meters as well as the long jump. Two years later, he won the 100, 200 and long jump at the U.S. national championships, the first person to achieve this triple since Malcolm Ford in 1886.

The 6-foot-2, 173-pound Lewis had even grander plans for the 1984 Olympics: four gold medals. First came the 100 meters. With a burst that was clocked at 28 mph at the finish, Lewis won by an incredible eight feet -- the biggest margin in Olympic history -- in 9.9 seconds.

Lewis captured the long jump with his first leap -- 28- into the wind. After fouling on his second attempt, Lewis, who had six races behind him and five more to go, passed on his last four jumps. The fans in Los Angeles didn't care about his heavy schedule; they booed him for not challenging Beamon's record.

Lewis won the 200 in a then-Olympic record 19.80 seconds and completed his quest by running a 8.94 anchor leg on the victorious 4x100 relay team.

But that L.A. gold didn't turn into as much green as Lewis had expected. The endorsements he had counted upon didn't come (at least in the U.S.; he did much better in Europe and Japan). Lewis was hurt by his own attitude, as well as by his agent comparing him to Michael Jackson.

No one had ever successfully defended either the long jump or 100-meter title in the Olympics. Lewis won both in 1988. Competing in the long jump final just 55 minutes after he qualified in the preliminaries of the 200, Lewis finished first with a leap of 28-7.

In the 100, Lewis was beaten to the finish line by Ben Johnson, who ran a remarkable 9.79 seconds. But the steroid-using Canadian was stripped of the gold medal for failing a drug test, and Lewis was moved up to first. His 9.92 seconds was listed as the world record.

Lewis, whose two-year winning streak in the 200 had been snapped at the Olympic Trials when he was beaten by training partner Joe DeLoach, was overtaken in the '88 Olympic 200 by DeLoach with 30 meters left and lost by .04 seconds. Lewis never got an opportunity to go for the gold in the 4x100 as the U.S. was disqualified in the first round (without Lewis) for an improper baton pass.

The 1991 World Championships in Tokyo were quite incredible -- in both the 100 meters and long jump. Lewis won one and lost the other. In the 100, six runners broke 10 seconds, with Lewis leading the pack after a mighty finish. "He passed us like we were standing still," said runner-up Leroy Burrell.

For the first time in his life, after going undefeated in the long jump for a decade, after winning six Olympic gold medals, Lewis had at last set an untainted, unshared world record (since broken) with his 9.86 seconds. "The best race of my life," Lewis said. "The best technique, the fastest. And I did it at 30."

But Lewis' 10-year unbeaten streak in the long jump came to an end five days later, even though he put together the greatest series of jumps in history. Lewis had never before reached 29 feet, and this day he did it three times, including 29-2 (wind-aided) and 29-1 (against the wind). But Mike Powell, who had lost 15 consecutive times to Lewis, unleashed the longest jump in history -- 29-4.

At the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona, Lewis exacted revenge on Powell, who had the record that Lewis craved, when he edged him by 1 inches with a leap of 28-5. Lewis won his eighth gold medal by anchoring the record-setting 4x100 relay team.

But eight wasn't enough for him. Lewis, who qualified third in the 1996 Olympic Trials in the long jump, showed he still had one huge leap left in him. His 27-10 at Atlanta was his longest jump at sea level in four years.

"Lewis beat age, gravity, history, logic and the world at a rocking Olympic Stadium in Atlanta to win the Olympic gold medal in the long jump," Reilly wrote. "It was quite possibly his most impossible moment in an impossibly brilliant career."

Carl Lewis

(Source : http://trackandfield.about.com)

Born in 1961, in Alabama like the legendary Jesse Owens, Carl Lewis was a late developer physically. Whilst still a puny youngster of 12, he was introduced by his father to Owens who became his source of inspiration. The metamorphosis took place in 1976; after a ten centimetres growth spurt, Lewis ran 100 yards in 9.3. He enrolled in Houston University in 1979 and began to be coached by Tom Tellez who was soon to say of Lewis: "He had a brain like a computer and mastered all the essentials of sprinting and the long jump." His long reign began after being denied his first Olympic experience by the US boycott of the Moscow Games.In 1982 he jumped 8.76m and had a narrow foul of 9.14m (over 30 feet). Despite remaining unbeaten for ten years - 65 straight victories - he was unable to equal Beamon's 8.90m world record before Mike Powell beat him to it in 1991.

Three times Olympic long jump champion, Lewis (1.88m and 78 kilos) equalled Jesse Owens' great exploit by winning four gold medals at the 1984 Games in Los Angeles. "I suddenly felt very, very big," he said at the time, "very strong, as though I had just conquered the world." Lewis remained an athletics star, even if it took Ben Johnson's disqualification for doping in Seoul to give him his second Olympic gold in the 100m. Lewis set a splendid world record of 9.86 to win the 1991 World Championships 100m title. A year later, he won two more Olympic golds in Barcelona. Then, his hand on his heart on the podium, he shed a few tears, as if, having reached the heights of Olympus.

Lewis' crowning glory was to come in the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta where he achieved yet another victory in the long jump after failing to qualify for the 100m and was excluded from the 4x100m relay team amid much discussion.

His Olympic gold medal total of nine equalled that of the great Paavo Nurmi.

Carl Lewis: Not Just An Olympic Champion

(Source : www.kentuckyconnect.com)

By Rich Hofmann

Knight-Ridder Newspapers

ATLANTA (KRT) -- First came the ceremony, then the pictures. Carl Lewis, with a gold swoosh in his lapel and a smile plastered on his face, actually seemed to enjoy the process.

Ceremony, pictures, then interviews -- a dozen or more satellite things, with Lewis staring at a camera and speaking to some disembodied talking heads from local stations all over the country. The subject was organ donation. It is a topic on which Lewis speaks with passion.

"I don't think you'll find anybody more dedicated or more genuine than Carl Lewis when it comes to this cause," said Wendy Marx, who contracted Hepatitis B in 1989 and almost died waiting for a liver transplant. Now, seven years later, she leads a foundation whose goal is to highlight the need for people not only to sign organ-donor cards, but to discuss their wishes with their families.

The Wendy Marx Foundation has joined with the Mickey Mantle Foundation to print donor cards carrying Lewis's picture, following the original cards bearing the likeness of Mantle, who died last summer from cancer a month after he underwent a liver transplant.

"Carl's been there since the start," said Marx, whose brother Jeffrey Marx helped Lewis write his 1990 autobiography. "He was the only person, besides my family, to stay with me in the hospital when I was in a coma waiting for a liver."

"My first introduction to her was when she was in a coma," Lewis said. "That's pretty strange in itself."

"He was sleeping on the floor with my family in the CCU (critical-care unit)," Marx said. "That's dedication."

"We called it `The Cave' at the time," Lewis said. "I slept on the floor, next to all of them. I went through it with them. You get to understand what it's like, the waiting."

"Not many people know that about Carl," Marx said. "He's not just an Olympic champion athlete. He's really a champion person."

If that is the reality, the image doesn't match. The image -- of ego and self-absorption -- was drawn long ago. True or not, it endures.

Lewis has won eight gold medals at three Olympics, but he still is significantly more popular outside the United States than he is at home. He is already spoken of by some as the greatest athlete of the 20th century, yet he continues to strive for one more Olympics despite being written off as done, washed up, by the track cognoscenti.

It is a complex picture.

Then again, it always has been.

"I don't give free rent upstairs," Lewis said. "You have to earn your spot in this brain."

Translation: He doesn't care what anybody thinks anymore.

Lewis has enjoyed the privilege of international notoriety for more than a decade. At the same time, he has endured what seems to be a quadrennial reconfiguring of his public persona. You mention it; he smiles.

"So be it," he said. "First I was the boy wonder, the kid. Then there was the middle of my career. Now it's starting to be almost like I'm people's grandfather. It's like, `That's old Carl.' But that's how things evolve. I like it because it's shown that I've been able to mature as a person as I've gotten older. Life has changed for me. I've experienced more things. It makes me better.

"A lot of people worry about it, but I'm very proud of my age. To be an African-American male and 34 and have success, that's something to be proud of. I'm proud to be 34. I'm going to keep fighting, keep kicking."

He is the best athlete most of us have ever seen, or ever will see. Eight gold medals, one silver. Four U.S. Olympic teams -- including the 1980 team that didn't travel to Moscow because of a political boycott ordered by President Carter. Four gold medals at the '84 Games in Los Angeles -- tying the feat accomplished by the legendary Jesse Owens at the '36 Games in Nazi Germany.

That part of it is unquestioned. The athletic, on-the-track greatness -- and the longevity -- of this kid from Willingboro, N.J., is really unrivaled in his sport, and maybe in all sports. So good, for so long. That should be the legacy -- simple, sustained greatness. That would be the legacy if Lewis had competed in a different era, a less media-saturated era.

But he didn't. He competes in these times. And so, we saw him try to do the singing thing, and the dancing thing. And we heard his manager, Joe Douglas, make comparisons between Lewis's earning power and that of Michael Jackson. And we read the snippets of cattiness that came from some rivals. And, just recently, we saw the ads for an Italian tire company in which he wore those red spiked heels.

Over the years, the scrutiny has been enormous. As Lewis said, "I'd cut my hair and people would say, `Oh, my God, what are you doing?' I never understood that. All I did was cut my hair. It was amazing."

Some of it was a long time ago. There were the '84 Games themselves, so successful, so controversial. Remember, he was actually booed by many at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum because he settled for the gold medal and didn't try to break the long jump world record; a cool night, a bum leg, more events to run, it didn't matter. Another time at that Olympics, when he accepted an American flag from someone in the stands to wave during a victory lap, people wrote the fantasy that the whole thing was staged.

He was a big target, and few adversaries missed. The image survives, to some degree, even as Lewis makes his final -- many believe futile -- Olympic run. Lewis shrugs at the image question.

"Nothing I can do about it," he said. "When I leave, I hope I leave some of the things we fought for. I hope my legacy is that we helped change the sport financially, and we helped zero in on the drug problem. That's what I stood for the most throughout my career. Those are the two issues I hope stay strong.

"Obviously, the sport is going to evolve and other people are going to take over and get notoriety. I just hope that there are more."

Michael Johnson, the world champion at 200 and 400 meters, has begun to assume the mantle.

"The days of having a Carl Lewis and a Jackie Joyner-Kersee do it are really over," Lewis said. "In order for this sport to grow, we need people like Michael Johnson. He's tremendous. I just hope we get him and more athletes. We're going to need more of a committee to do it in the future because the sport needs that attention."

Johnson, for his part, has talked about how Owens was the greatest track athlete of all time, not Lewis, because of the racism that Owens had to overcome in the '30s.

Again, at the recent USA Mobil Indoor Track and Field Championships at the Georgia Dome, Johnson said, "Carl Lewis is definitely on (a high) level, but Jesse Owens is definitely on the top. He'll definitely always be the greatest athlete who ever ran track. My goal is just to be one of the best."

A subtle rivalry as the baton passes.

There is always this undercurrent surrounding Lewis. Whether it's his own doing is open to debate. But the existence of the undercurrent is not. Nothing is simple and clean.

Take the whole issue of the health of track and field in the United States. Lewis and his club, the Santa Monica Track Club, have feuded with U.S. track officialdom seemingly forever. Lewis has been critical every step of the way, as track has become, in many American minds, a once-every-four-years sport.

It continues. Recently, when asked if he was disappointed in the current marketing of U.S. track, Lewis laughed and said, "It's hard to be disappointed when you can't find it at all."

He has pushed for better treatment of athletes over the years and seen some gains. He has also formed a foundation that offers financial assistance to needy athletes; one of them, Jenny Spangler, just won the U.S. Olympic trials in the women's marathon.

But Lewis also has thrown around his considerable influence in the free market over the years to demand and receive large fees for appearances. And here's the question: Did that set a standard for the circuit, or just take a limited amount of purse money out of the pockets of less-influential runners?

Questions. They abound. In most cases, though, Lewis can fall back on the fact that truth is a valid defense. Yes, yes, it was a little tough to watch when Lewis chose the 1987 world championships in Rome -- a meet at which Ben Johnson blew past him to set the world record -- to accuse Johnson of using performance-enhancing drugs.

But then, the next summer -- after Johnson filled the most-famous specimen bottle in Olympic history, after Johnson was stripped of his gold medal in the 100 meters and it was awarded to Lewis -- well, what could you say? Lewis was right all along.

"I was criticized heavily for it," he said. "A year later, it went from, `You're a crybaby, you're a crybaby,' to, `You're a prophet.' "

Back and forth, definition and redefinition.

That, too, is the man's legacy.

"There is no emotion to my competition," Lewis said. "I focus on doing specific tasks. That's it."

The task at the indoor championship meet in Atlanta was to work on his start, Lewis said. It wasn't to run fast. There would be two preliminary heats in the 60-meter dash and the finals. Lewis was hoping to get three shots out of the blocks.

Instead, he got one.

Instead, Lewis finished dead last in his heat.

"I'm disappointed I didn't technically get out of the blocks well," he said. "Now, obviously, I have to get faster. What it's going to take is running faster things."

There were few believers among those listening. Lewis hasn't run under 10 seconds in the 100 meters since 1991. He has been hurt a lot in the intervening years. But he's also older. There's no denying the calendar, although he has managed to do it longer than most.

So far this year, he had run two indoor 60-meter dashes. He has finished last in both. He has been training with weights, with a medicine ball, with more distance running. His body fat is said to be down to 3 percent. He says he feels good. He says his intention is to try to qualify for the U.S. team at 100 meters, 200 meters and in the long jump, but that he could only realistically compete in the long jump and one other event at the Olympics.

Many believe he will make it to his fourth Olympics as a long jumper. Almost no one believes he will make it again as a sprinter -- although, well, listen to Jon Drummond, one of only nine Americans who ever ran 100 meters in less than 10 seconds.

"He's the best in our division," Drummond said. "People look at a runner's time now when they should look at his experience. It's not time to run fast now.

"I give Carl respect. He's got a magic wand. He always waves it at the big events. Maybe this wasn't a big event for him."

Clearly, the Atlanta meet wasn't. And, just as clearly, only what happens at the June trials and the Olympics themselves matters. But why bother at this point? Why not relax? Why not settle into a career of community work and public speaking, which you say is next on your agenda?

Why risk it?

Why finish last in public?

"When I was a young kid, I was the slowest one on the block and the slowest one in the class, the slowest one everywhere -- even in my family," Lewis said. "My inspiration was just to run faster. Everything else happened afterward. I think it's your heart and passion. My heart has never left. I'm a person who loves to compete and likes to train and likes to be in shape. When I get out there, I do the best I can to be the best I can .

"At this stage of my career, I've had a lot of success. Now it's time to challenge myself, to be the best I can be. My drive is not to win the gold medal, per se. It's to push myself to the limit.

"I have nothing to prove," he said. "Nobody expects anything. If I win, it will be a great accomplishment. If I don't win, it'll be a great accomplishment because I challenged myself."

He was chatting easily now, taking a few minutes between satellite interviews. The appearance on behalf of the organ donation people was almost over. The unsuccessful race at the Georgia Dome would be the next day.

A few minutes earlier, there had been a question to Lewis about what organ he would pick to donate. First, he joked about his poor eyesight. He thought some more. Then, this:

"I think my heart," Carl Lewis said. "I've worked hard at that."

Olympics - Carl Lewis

11/88

(Source : www.forerunner.com)

SEOUL, Korea (EP) - On the day that Carl Lewis found out he was the Olympic gold medal winner for the 100-meter sprint - the second time in a row he has won the gold for that event - the U.S. track star appeared at the largest church in the world to share his saving faith in Christ.

At the Yoido Full Gospel Church in Seoul, Lewis was the star attraction of the televised "Evening with the Olympians," sponsored by Lay Witnesses for Christ. With the help of an interpreter, Lewis told the 15,000 evangelical Koreans who were present that his faith in Christ has been his source of strength through the challenging and trying times of his life, including the death of his father 18 months ago.

"Eighteen months ago, my father passed away from cancer," Lewis explained. His father, Bill Lewis, was a high school teacher and coach in Willingboro, New Jersey. "We were extremely close and it was a very, very, very difficult time. I would not have been able to handle it without faith ... When my father died, I buried the 100-meter gold from the 1984 Olympics with him. He inspired me to go on and become the best I could be in the '88 Olympics."

Lewis, 27, became the recipient of the 1988 gold medal when Ben Johnson, the Canadian athlete who finished first in the 100-meter sprint event, tested positive for steroids, a banned substance for Olympic athletes. In a prepared statement, Lewis said "I feel sorry for Ben and for the Canadian people. Ben is a great competitor and I hope he is able to straighten out his life and return to competition."

Because of Johnson's expulsion from the Olympic Games, Lewis became the first sprinter in history to successfully defend a 100-meter Olympic victory, just as he became the first long jumper to win two Olympic gold medals in a row.

Lewis said that after the 1988 100-meter event, when he placed second after Johnson, "I was satisfied because I'd given my best effort. We know the Lord speaks to us in many ways." Then he recounted a dream his mother had about the event. In the dream, Lewis' father told his mother to tell the younger Lewis that whatever the outcome of the race, "to not worry about it because the Lord said everything's going to be all right."

"So today we found out that it was," he said.

Carl Lewis

(Source : www.media.mcdonalds.com)

Carl Lewis is regarded by many as the greatest Olympian of all time. Having made every U.S. Olympic team from 1980 through 1996, Carls five Olympic appearances set the record for male athletes. Carl has competed in some of the most difficult sporting events, including the long jump, the 100 meter, 200 meter and the 4x100 meter relay. Many of his Olympic performances were in world or Olympic record time.

Carls stunning Atlanta Olympics win gave him his fourth consecutive gold medal in the long jump and ninth gold medal overall. Both of these feats are Olympic records. Carl is only the third track and field athlete to win four medals in one Olympic Games and the second Olympian to win the same event in four consecutive Olympic Games.

Remarkably, Carl had a decade-long winning streak in the long jump; a streak that gave him 65 consecutive long jump wins.

Since his retirement from competition, Carl has combined his athletic success with his personal interests in entertainment, business and charity.

In 1985, Carl was inducted into the United States Olympic Hall of Fame.

Born in 1961, Carl was raised in Willingboro, N.J. Both of Carls parents were track coaches. As a young man, Carl spent his early working days as a McDonalds crew member in New Jersey. Carl currently spends time at his residences in Houston, Texas and Los Angeles, California.

GREAT OLYMPIANS

(Source : www.greatolympians.com)

Name Carl Lewis

Nationality USA

Born 1961

Events 100m

200m

Long jump

4x100m relay

Personal Bests: 100m 9.86sec

200m 19.75sec

Long jump 8.87m

Olympic Titles: 100m 1984 & 88

200m 1984

Long jump 1984, 88, 92 & 96

4x100m 1984 & 92

World Titles: 100m 1983, 87 and 91

Long jump 1983 and 87

4x100m 1983 and 87

Carl Lewis, real name Fred Carlton Lewis, has won 9 gold medals at the Olympics, and holds a strong claim to be called the greatest Olympian ever. His Olympic story began with his Jesse Owens equalling feat in 1984, winning 4 gold medals in 100m, 200m, long jump and the 4x100m relay.

In 1988 he successfully defended his 100m title but did not actually win the race. The winner Ben Johnson was stripped of his gold medal for using anabolic steroids, and the title handed to second placed Lewis.

However, his most impressive achievement was winning 4 Olympic long jump titles back to back in 1984, 88, 92 and 96, equalling Al Oerter's record. Lewis did not achieve one of his aims to break Bob Beamon's long jump world record; that honour went to his great rival Mike Powell who won the 1991 World Championship, Lewis first competitive defeat for 10 years.

Despite these amazing feats Lewis often found his outspoken comments made him unpopular with other athletes and even with the American public, but his tally of Olympic and world titles will be hard to beat.

|

|

|