|

|

CLICK ON THE PICTURE TO GO TO 'JACKIE CHAN SING LUNG..ALREADY A DRAGON'...A JACKIE CHAN FAN SITE

BIOGRAPHY

Name : Jackie Chan

Cantonese : Sing Lung

Mandarin : Cheng Long

Born : April 7th, 1954

Zodiac Sign : Horse

Height : 5'9"

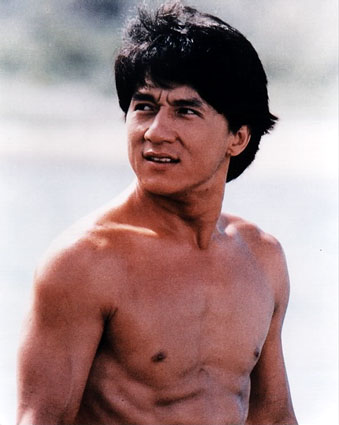

The early years...

Jackie Chan was born Chan Kong-sang (which means "Born in Hong Kong" Chan), April 7th, 1954, the Year of the Horse. Jackie was the only son of Charles and Lee-lee Chan, who were very poor and worked for the French ambassador to Hong Kong. Charles was a cook and a handyman, while Lee-Lee worked as a housekeeper. They lived in a room in the mansion of the French ambassador on the exclusive slopes of Victoria Peak in Hong Kong.

Most babies are born nine months after being conceived. Jackie, on the other hand, stuck around an extra three months, so his mother had to have surgery to bring him into the world. Because Chan Kong-sang weighed 12 pounds at birth, his mother nicknamed him "Pao-pao", wich is Chinese for "cannonball". The bill for his mother's surgery came to HK$500 (about $26 US), and his parents' savings didn't come close to covering the cost. But the lady doctor who performed the surgery approached Jackie's nervous father with a deal. She had no kids of her own, she explained to him, and she knew he and Jackie's mother, Lee-lee, had no money. If Charles would allow her to "adopt" him, she would be willing to pay for the costs of the surgery and his mother's hospital stay. But Jackie was his parents' only son. He was their symbol of their new start in Hong Kong. Charles' friends lent him the money to pay off the hospital dept, and thanked the doctor for her generous offer.

The Peking Opera School...

In 1960, Charles had to move to Australia to work in the Chinese embassy there. It was at this time that Jackie was first enrolled in the Peking Opera school. Chan was to study there from the age of six/seven until the age of seventeen -ten years. Jackie's master at the school was Master Yu Jim-Yuen, to whom Jackie owes his entire career. There Jackie's name became Yuen Lo.

At the school, students were taught traditional Chinese arts of performing, singing, acting, and especially acrobatic and martial arts. Any number of traditional Chinese martial arts were taught, along with weaponry, stick fighting and the like. Students were forced to put in eighteen hour days and subjected to grueling physical demands, for example, holding headstands or stances for hours at a time. Beatings were very common. After some years, when Jackie's mother joined his father in Australia, Master Yu adopted Jackie, making him his godson. Jackie was invited to join "The Seven Little Fortunes", a performing group at the opera which performed at several locations in Hong Kong.

Many of Jackie's modern day co-stars also came from the Peking Opera School. Some of them are huge stars in Hong Kong today, including Samo Hung, Yuen Biao, and Yeun Wah -- the list is long! Samo Hung and Yen Biao have co-starred with Jackie several times, including the movies Winners and Sinners (Five Lucky Stars), Project A, My Lucky Stars, and Twinkle, Twinkly Lucky Stars to name just a few.

Jackie's first onscreen appearance came in 1962, when a director offered him a small role as a child actor in the Cantonese film Big and little Wong Tin-Bar. Jackie would go on to appear in several films, first as a child actor and then as a stuntman, before the age of seventeen

Jackie the stuntman...

At seventeen, Jackie left the Peking Opera and found small roles in films. His first leading role was in 1971's Master with the Cracked Fingers, a fairly standard tale of revenge. In 1973 Jackie worked as in extra in two films that starred the biggest name in Kung-Fu movies at the time -Bruce Lee. In Fist of Fury (The Chinese Connection), Bruce kicks Jackie through a building wall. Apparently, Jackie thew himself through the wall with no padding and with such vigor that Bruce was forced to ask if the young stuntman was all right.

Jackie was all right, and later that year appeared in Bruce Lee's breakthrough classic Enter the Dragon, again as one of the numerous people Bruce fights off. Although only on the screen briefly, Jackie's face can clearly be seen.

Lo Wei film company...

In 1976, after appearing in the film Hand of death (Countdown in Kung Fu), directed by a young John Woo, Jackie went to Australia a short while to be with his parents. He returned to Hong Kong the same year, and was signed as a lead actor by the Lo Wei film company. This is when Willy Chan became Jackie's best friend and personal manager, wich he still is today.

Jackie, who had been acting at this time under the name "Chen Yueng Lung" was renamed "Sing Lung" (means "already a dragon" or "become the dragon"), and in 1976 made his first film for Lo Wei, titled New Fist of Fury, a sequel to Bruce Lee's Fist of Fury (The Chinese Connection). The film cast Jackie in a Bruce Lee type role, and although Jackie's martial arts talent are exhibited, Jackie was not comfortable acting in Bruce's shadow. Jackie would go on to make a number of films for Wei, none of which were huge sucesses.

How Chan Kong-sang (Yuen Lo) became Jackie Chan

In 1976, after joining his parents in Australia, he decided he had to work to earn some money while he was there. Therefore, one of his father's friends, a guy named Jack, took Yuen Lo to a construction site to work. Jack knew that Kong-sang wasn't a name the Australian workers would get an easy grip on. "Aw, hell, his name's Jack, too," he said to his fellow workers. Over the months Jackie stayed there, "Jack" became "Jackie". And that's how Jackie Chan was born.

New try at Seasonal Films...

In 1978, Jackie was loaned to director Ng See Huen's Seasonal Film company for the film Snake in Eagle's Shadow. Unlike his previous films, the film had a light, humorous tone, better acting, and a better story. Free of the burden of trying to be like the late Bruce Lee, Jackie's expressive features, timing, and great comedic ability began to show themselves. The film was a hit in Hong Kong, and the cast and director reunited shortly thereafter to make the even more successful Drunken Master, which broke all the box office records in Hong Kong at the time. Jackie finally began to go off in a different direction, away from the style of Bruce Lee, and into his own clowning Kung-Fu style.

The wanted breakthrough...

The success of Drunken Master gave Jackie more control over his films, and he directed and choreographed his next, and last, film for Lo Wei, 1979's Fearless Hyena. Following that film, Jackie realized he had to extricate himself from the meager talent of Lo Wei, and signed with Raymond Chow's Golden Harvest film company. However, this breach of contract angered Wei, who together with the Triads issued threats on Jackie Chan's life. To avoid any messy problems, Jackie was sent to America, where he was to try and break into the U.S. market. He made Battle Creek Brawl, which was a big flop, mostly because Jackie didn't get the chance to do the style he wanted. Instead of a hillarious Kung Fu artist, Jackie was a Chinese kid in America's 1930s. Jackie would also return to America in 1981 and 1984 to fill a small role as a Japanese driver in the Cannonball Run films. Jackie was bought out from Lo Wei at the amount of HK.$10 000 000 by Golden Harvest studio heads Raymond Chow and Leonard Ho. Jackie was free to return to Hong Kong.

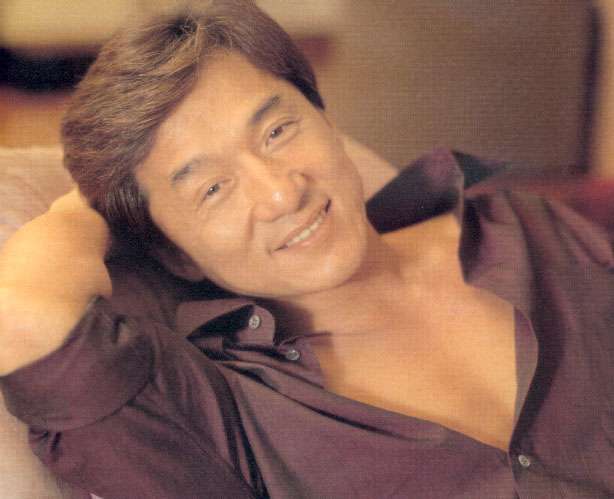

Jackie Chan's World...

Jackie's trip to America was not a total waste, as he was first exposed to early American silent film stars like Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton. Admiring their movement and timing, as well as their stunts, he realized that movement and physical control could lead to spectacular action scenes and communicate often better than words. His 1984 film Project A, set in early 1900's Hong Kong about rivalries between the police and coast guard, took him away from the traditional Kung-Fu genre and into a new direction. The film delivers tightly choreographed martial arts and physical humor as well as stunts. Jackie goes so far as to recreate Harold Lloyd's "hanging from the clock tower" stunt, falling three stories afterward. It was around this time that Jackie's stunts begin to get more spectacular, and to connect with the audience, Jackie performs them all himself, which would eventually become his trademark.

In 1983 Jackie appeared in the Samo Hung directed comedy Winners and Sinners. Jackie, Samo, and Yeun Biao had become good friends studying at the Peking Opera together, and each achieved individual stardom in the Hong Kong movie scene. Jackie considered Samo to be his "big brother" and Biao to be his "little brother". The three would go on to make seven movies together. In 1987 after the film Dragons Forever the group had a bit of a falling out over their direction, and have not appeared together in a film since. In 1996 however, Jackie and Samo reunited to make the film Mr. Nice Guy.

In 1985, Jackie again attempted to break into the American market with the film The Protector. The director attempted to make Jackie into a Clint Eastwood type character, and the film wasted not only Jackie's comic abilities, but his martial arts abilities as well. Disillusioned with the American style of filmmaking, Jackie returned to Hong Kong and directed and starred in the smash hit Police Story. This was a huge smash-hit, and the film featured the most dangerous stunts attempted up until that time, as well as incredible fight scenes, smashing unbelievable amounts of glass. Jackie would go on to make 4 sequels.

From there came hit after hit, including Armour of God, Project A II, Dragons Forever, Police Story II, Miracles: Mr. Canton and Lady Rose. All these films feature fast, tightly choreographed fight scenes and dangerous stunts. While filming The Armour of God Jackie fell from a tree and hit his head on a rock causing a hole in his skull, a wound which he carries to this day.

Numerous hits followed cementing Jackie's position as Hong Kong's premier action star. In the mid 1980's Jackie formed his own production company "Golden Way", which in addition to Jackie's own movies, has produced such films as Stanley Kwan's "Rouge".

Jackie continued to make hits throughout the 90's, despite competition from more Hong Kong and American films. Jackie's films have taken on different directions, including teaming with action star Michelle Khan (Yeoh) in 1992's Police Story III: Supercop, and taking a more dramatic turn in 1993's Crime Story, based on the true story of a Hong Kong detective. In 1994, he starred in the film Drunken Master II, an in name only sequel which returned him to his early film making days. The final fight scene took months to film, and the result was spectacular. The film broke all box office records for Hong Kong, and reinvigorated Jackie's career. Taking a chance, American film company New Line Cinema bought the rights to distribute Jackie's next film in the United States. Titled Rumble in the Bronx, the film opened in February 1996. Heavily promoted by New Line, the film opened to excellent reviews and went to #1 at the box office the week it debuted. The film created a huge impact finally exposing the American public to martial arts moviemaking of a caliber they had never seen before, and winning Jackie Chan legions of new fans. Jackie had finally broken into the American market and was on his way to becoming a household name.

Following the success of Rumble in the Bronx, New line bought rights to Chan's successive works, while Miramax films bought up Jackie's recent 90's work to distribute in the U.S. Enjoying his newfound fame, Jackie has traveled to the United States often to promote his films, as well as continuing to promote his films around the world. After a lifetime in film, Jackie has developed his own unique style, impossible to capture in words, and visible only in the magic of his films. Concerning his place in film history, Jackie says- "I want to be remembered like I remember Buster Keaton. When they talk about Buster Keaton or Gene Kelly, people say 'Ah yes, they good'. Maybe one day they remember Jackie Chan that way. That's all".

(Source : www.jackiechan.com)

A. Magazine ranks Jackie no.7, out of "The 25 Most Influential Asians in America"

Article source: A. Magazine

In his second shot at Hollywood stardom, Jackie Chan's English-dubbed version of his Hong Kong hit Rumble in the Bronx smashed into the number-one spot, while winning over American hearts and minds (as well as winning him a tub of bronzed popcorn from MTV, who presented him with their Lifetime Achievement Award) The hyperkinetic Chan didn't rest on his laurels: He quickly followed the success of Rumble with yet another dubbed Hong Kong retread, SuperCop, and became a frequent--and funny-guest on Letterman and Leno.

PROGNOSIS: Chan, whose body has been bruised and broken innumerable times due to his stubborn determination to do all of his incredibly dangerous stunts on his own, can't keep up the rough-and-tumble output too much longer. Luckily, he's got a number of already-filmed flicks in the can, awaiting release in the States over the next few years--and meanwhile, the relatively forgiving nature of US action flicks means that he, like fellow middle-aged war gods Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger, has a chance at a second career on this side of the Pacific. Both of the aforementioned have talked about working with him, as has star director Ang Lee The king of kung-fu comedy's got a few tricks left in him yet.

PROFILE

Name: Jackie Chan

Birth Name: Kong-Sang Chang also known as Jackie Chan Sing Lung (which means 'Already a Dragon')

Height: 5'8

Sex: M

Nationality: Hong Kong/Chinese

Date: April 7 1954

Birth Place: Hong Kong China

Occupation: actor director producer

Education: Nan Hua Elementary Academy

Chinese Opera Research Institute (1961-1971)

Peking Opera School

Husband/Wife: Lin Feng-Chiao (aka Lin Feng Chow; Taiwanese; actress; married in 1983; separated)

Relationship: Elaine Ng (Miss Asia 1 daughter)

Father: Charles Chan (refugees from the Chinese civil war who worked as cook and housekeeper for the French ambassador to Hong Kong)

Mother: Lee-Lee Chan (now lived in Sydney Australia)

Son: J C Chan (born in 1982; mother: Lin Feng-Chiao)

Claim to fame: as Ah Keung in Rumble in the Bronx (1995)

FAN MAIL:

Willie Chan

Golden Harvest Ltd

Hong Kong

China

(Source : www.celebritywonder.com)

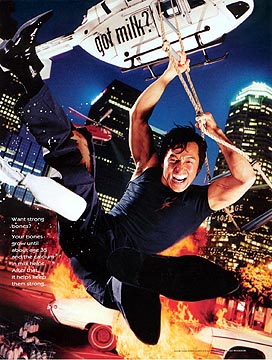

Chan the Man

Hollywood's toughest actor knows how to break chops, kick ass and make money!

At a castle in rural Yugoslavia, movie hero Jackie Chan stands atop a 40-foot parapet, ready to leap to the branch of an adjacent tree. AT this point in your standard Hollywood production, the director would yell "cut," and the star would return to his trailer for some catered lobster while a stuntman did the leaping. But this star is different: Chan, the sinuous ebullient Hong Kong Actor who has become tyhe idol of millions, always does his own stunts.

"I don't do special effects," the actor recently told Hong Kong Film Connection. "I don't do computers...It's not like Superman, Batman. Everybody can be Superman... But nobody can be....Jackie Chan!"

Modest he's not, but then, he's more than earned the right to crow. Back at the castle, Chan takes his leap into what is to become the most famous sequence in Armour of God, an Indiana Jones-like adventure about evil monks starring--and directed by--Chan.

The cameras catch it perfectly. Chan launches himself toward the branch. His hands fail to connect and his body flies downward through space, slamming into the rocks below. His head makes a direct impact. A portion of the right side of his skull implodes as if hit with a nuclear sledgehammer. His ears and nose pour blood like broken faucets. The film crew scrambles down to rescue him, rushing the crimson-soaked star to a primitive Yugoslav hospital where surgeons barely manage to save his life.

"I jump off castle wall, grab tree branch. Easy stunt," he tells a reporter, recalling the notorious incident. So easy they didn't even take the time to set up a safety net. It was the second take, at the insistence of perfectionist Chan. "I go one time -- fine. But somehow not feel quite right. Go again.... I miss the branch!"

A job-related accident such as this would be a signal to most people to think about retirement or another line of work. But Chan, as he likes to point out, is not most people. He didn't become the most successful and popular movie star on earth by worrying about little things like ruptured eardrums and a fractured skull that left a permanent crater-like indent at the top of his forehead. Indeed, Chan, like his fans, revels in these painful mistakes, showing them as "blooper" outtakes following the conclusions of his films. For the fans, these scenes are the most anticipated part of each movie: They see what wasn't supposed to happen--the broken leg, the burned flesh, the scrapes, crashes, and crunches, Chan and his costars and stuntmen being hurtled into an ambulance when an impossible stunt proves--impossible! All in a day's work for Chan. "It's very important I get hurt when I make movie!" he gleefully explains.

An international success for well over a decade, Chan's worldwide ticket sales make such rival action stars as Sylvester Stallone and Jean-Claude Van Damme pale by comparison. Only McDonald's has served more billions. But for years, the only people in America who got to see Chan's wild-and-wooly flicks were the denizens of big city Chinatowns and a smattering of cultists and adventurous film buffs. Now, in a little over a year's time, all of that has changed. Jackiemania has touched down in America at last--and Van Damme, Steven Seagal, and even Amold Schwarzenegger are beginning to look very tired to many. The Hollywood action movie may never be the same.

"To jump through glass, to jump off buildings, to be dragged behind buses, and direct at the same time," gushed Pulp Fiction boy wonder Quentin Tarantino at the 1995 MTV Movie Awards as he prepared to give Chan a Lifetime Achievement Award. "He is one of the best filmmakers the world has ever known!"

It all started with the 1996 U.S, theatrical release of Rumble in the Bronx, which surprised even Chan's greatest boosters by becoming the top-grossing film on its opening weekend. Those who thought Hong Kong martial arts movies were just campy Five Fingers of Death numbers from the '70s sat up and took notice. Neither the best nor the worst of Chan's dozens of vehicles, Rumble (in which the mountainous landscape of Vancouver, Canada, filled in for New York's battle-scarred borough) introduced American audiences to the world of Chan-shot full of high spirits, slapstick, dazzling fight scenes, and spectacular action. And seeing the success it had distributing Rumble, New Line quickly secured U.S. rights for Thunderbolt and First Strike, two more of Chan's major productions, while other companies grabbed up the three-year-old Supercop, as well as Crime Story, Drunkeut Master II, and the unreleased A Nice Guy, guaranteeing Chan's presence on American screens for several years to come. "Now," the star says, delighted that the last holdout country in the world has succumbed, "Jackie Chan is everywhere, you see!"

The man whose face is as familiar to the Chinese as Mao Zedong's, and who has been called the most successful actor in history, began life nearly sold off by his parents for the paltry sum of $26. Refugees to Hong Kong from mainland China, they needed money for food, for survival.

According to Bey Logan, author of Hong Kong Action Movies, "At the time he was born, his father was so poor he seriously considered an offer to sell his baby to one of the doctors. In fact, Chan wasn't sold until his seventh birthday. It was then that his mother was paid a token sum by Sifu Yu Chan Yuan to enroll her boy in his Peking Opera Academy."

The Peking Opera is a uniquely Chinese form of entertainment that has very little in common with the world of Pavarotti. These operas are brightly colored stage shows that feature death-defying acrobatics and spectacular martial arts displays, as well as drama, singing, dance, and comedy. Hong Kong's Peking Opera Academy is a legendary/notorious name in the British Crown Colony's popular culture. In it, contingents of Hong Kong children were consigned for ten years of rigorous training in the performing arts (few of the children were ever taught to read or write). Students at the Academy followed grinding regimes of gymnastics and martial arts fighting, non-stop, year after year, put through their paces by disciplinarian Masters who often bordered on the vicious.,br> Living conditions? The Academy made a Dickensian orphanage look like Club Med. "It was bad," Chan told Logan. "If I tell you how bad it was maybe you won't believe me. If you didn't train hard enough you were beaten. At night we all slept under one blanket. That blanket! Dog had slept on it!"

Under these mean circumstances Chan's extraordinary strength, agility, and fearlessness were forged. So too were his lifelong associations--a brotherhood really--with the others under that filthy blanket. Some of them--Samo Hung and Yuen Baio, for instance--became fellow mainstays of the Hong Kong film world. His former master would later remark that Chan was by no means the best of his students, but, he added, "One of the naughtiest, yes."

Chan was made part of a troupe of boy stage performers known as the Seven Little Fortunes. Even as Chan trained for it, the elaborate Peking Opera was dying out as a popular form of entertainment and the burgeoning Hong Kong film industry was becoming a much more likely source of employment for the fearless Academy graduates. Chan actually made his first appearance in a motion picture (a family drama called Big and Little Wong Tin Bar) at the age of eight in 1962, his small salary going directly to his Master.

It was the early '70s when Chan went out on his own looking for work in the movie business. He began in cheap action pictures, doing stunt work. Gradually he moved up to supporting roles. The Chan of this period cut a very different figure from today's idol of millions. Far from showing off his comedic flair, he was often cast in villain parts. He also looked considerably different: scrawny of build with bad teeth, a pencil mustache at times, and narrowly slit eyes (according to Logan, Chan underwent an "eye-opening" operation in 1977, common among Chinese film stars).

Hong Kong's film industry was increasingly busy, but largely primitive in style and aspiration, churning out mostly low-grade formulaic kung fu actioners for local consumption. Then came the exception to this rule, and it was a big one Bruce Lee had returned to Hong Kong after very modest success in Hollywood and proceeded to turn the local picture business upside down. His breathtakingly brutal and kinetic action films put Hong Kong movie making on the international map and made the idea of an Asian superstar a reality.

On two occasions Chan got to work with The Dragon himself, getting quickly and brutally dispatched in fight scenes in Fist of Fury and Enter the Dragon. The past and present superstars were amicable on the set but never became close; at the time, their status was far from equal. Asked for his memories of Lee during a recent on-line interview, Chan responded, "I was a stunt man. We worked for the same company. I was always following and watching. But there were always people around him." His most vivid memory of working with Lee: "One day he gave me a great kick. He asked me if I was fine and I said,'OK.' "

Then, after only four sensational starring vehicles, Lee was dead. Hong Kong producers wondered, Who could replace him?

Chan's career had been floundering; he was ready to give up the film business and join his parents in Australia, where he hoped to start a new life. Then Hong Kong producer Lo Wei, a former associate of Lee's, signed him to do a sequel to a Lee hit, calling it New Fist of Fury.

Unfortunately, New Fist and the films that followed it in rapid succession were flops. The problem as Chan saw it was that his producer was forcing him to try and fill the dead Dragon's shoes. "Nobody can imitate Bruce Lee," Chan told Hong Kong Film Connection. "He wants me to do the same kick, the same punch. I think even now nobody can do better than Bruce Lee.... After he died nobody as handsome, right? So I tell Lo Wei that I want to change, but he won't listen to me. He just follows his style.... In the movie he wants every girl to love me. I'm not a handsome boy, not James Dean. I'm just not this kind of person. It's totally wrong, and none of them are a success."

Chan's brief moment in the limelight seemed about to fade when he was given the lead in a Seasonal Films production called Snake in the Eagle's Shadow. The story dealt with an exuberant kung fu student and his unconventional old master. Sensing that this was perhaps his last chance for success, Chan was determined to avoid doing another grim Bruce Lee imitation in favor of something higher spirited and closer to his own fun-loving persona.

"I kid around, totally opposite to Bruce Lee. When Bruce Lee acts like hero I act like underdog. Nobody can beat Bruce Lee, everybody can beat me. He's not smiling, I'm always smiling."

After so many years of Lee's ferocity and the deadpan pieties of the historical kung fu actioners ("chop-sockies" as U.S. critics derided them), Chan's slapstick martial arts innovation and the warm lovable character he brought to the screen made Snake in the Eagle's Shadow a smashing success.

His "drunken kung fu" style of fighting and subsequent comical inventions were exhilarating fun, an irreverent rethinking of martial artistry. The fights were still at lightning speed and intensity, but caused audiences to laugh and jump in their seats rather than groan and shudder. In Chan's battles, the hero didn't so much break the villain's bones as avoid getting his own broken through the performance of startlingly fast evasive movements and feats of physical dexterity. Instead of the classic martial arts weaponry, Chan used whatever prosaic objects he could lay his hands on. It was kung fu brought down to earth and then elevated again through the sheer grace and style of the performer.

As the South China Post put it in a tribute to Chan, "So successful was he that Chan can be said to have revitalized the entire Asian film business. Many producers and their stars tried to imitate Jackie's new genre of comedy kung fu, but all came to realize that Jackie Chan--like Bruce Lee before him--was one of a kind, inimitable."

Following the marketing strategy used with Lee, Chan's studio, Golden Harvest, rushed to put him into an American co-production. They hired Robert Clouse, the American director of Lee (there was just no getting away from him) in Enter the Dragon. But The Big Brawl, released in 1980, was a bomb, as was the semi-American-made The Protector. About his appearance in Cannonball Run and its sequel, the less said the better.

Chan went back home. But the American experience, if unsuccessful, had given him some fresh ideas for settings, story lines, and stunts. A sword-fighting swashbuckler that had been planned for him in the States would inspire Project A, his turn-of-the-century romp about young marine Dragon Ma battling South Seas pirates. His cops-and-crooks flop, The Protector, would later be "done right" as the delirious action masterpiece, Police Story. No longer cheaply made chop-sockeys, Chan's increasingly expensive productions would bloom in budget and ambition, often moving out of Hong Kong's cramped quarters to spectacular locations in Malaysia, Spain, Australia, and the Sahara Desert.

But the most dynamic change Chan introduced in the '80s was inventive and outrageous stunts--stunts like no star had dared perform since the high-flying days of silent movies, when Harold Lloyd hung from actual skyscrapers and Douglas Fairbanks, Sr., did handsprings from castle walls. Chan noted another silent movie influence. "What I learn, I learn from Buster Keaton," he told Australian reporter Barrie Pattison. "What a surprise, Buster Keaton! He do everything, makes me very surprised." In Project A, Part Two, Chan did a direct homage to Keaton, recreating a legendary gag from Steamboat Bill, Jr. As an actual wall of a building falls over him, Chan positions himself right below an open window and misses--by inches-being crushed to death.

Of his stunts, Jackie told Videoscope, "Don't worry about me. When I design all the choreography and fighting stunts, I know how far I can go."

Right. Making Project A, he suffered a bone-breaking fall from a clock tower. Working on Drunken Master II, his arm caught fire after he dragged himself over live hot coals.A Nice Guy resulted in a two-story fall that nearly snapped his neck in half. He suffered a broken ankle for Rumble in the Bronx. He was hit by an out-of-control helicopter filming Supercop. And, of course, there was the Armour of God accident that put a permanent dent in his skull. The truth is, Chan's injuries and near-disasters have become as much a part of his appeal as his irrepressible personality and physical skill.

He shrugs it all off as the price to pay for some really good pieces of film. "I get hurt," he told Entertainment Weekly, "but the movie gets released for one hundred years. OK. I broke my leg three months!"

With his worldwide popularity and the undeniable entertainment value of his films, it seemed inevitable that Chan would one day break through in the United States. Before Rumble, importers found buyers for his laser disks at over $100 a pop and video bootleggers did a brisk business in unlicensed Chan titles. In Hollywood, fans like Tarantino and Oliver Stone sang his praises. For years, the films of Stallone, Van Damme, and others recreated--stole ?--whole action sequences from his films. But why settle for second-best, his American followers asked, when you can get the original? Chan himself, burned by his first attempt at success in America, appeared uninterested. But lacking a foothold in the prestigious U.S. market must have been a serious thorn in his side. Then came the news that the mini-major studio New Line had decided to take a shot at breaking Chan with his American-set Rumble in the Bronx, which had broken box office records in Asia. New Line marketing chief Chris Pula told Time magazine that after all the "seven-foot Aryan walls of muscle" seen in Hollywood action pictures, Chan was "a breath of fresh air." The film earned $9.9 million on its opening weekend and became the first Chinese film and one of the few foreign films ever--to make Number One at the American box office.

Chan returned to America and was, for the most part, treated with respect and adulation. MTV honored him and the Oscars saw him present an award standing beside Kareem Abdul-Jabbar (Chan told GQ magazine: "Hong Kong media keep asking, ''Why Oscar put tall people in front of Jackie Chan? Make our yellow people very short? Why Oscar want to destroy Jackie Chan?' But that was my idea!"). Chan did Leno, Letterman, and any other show that asked him. Though for the most part he played the affably cool clown, Chan occasionally let slip to interviewers his feelings about the tame state of Hollywood action films. Hollywood, he derided, still used "sixty-year-old Clint Eastwood" for such roles. "Van Damme can knock me down for one second," he said, "but on the street he cannot chase me." He also felt U.S. stuntmen were a little too slow for his tastes.

"In Hong Kong I can hit one of my stuntmen--bam-bam- bam-and he will block every punch. American stuntmen...I hit--bam-bam-bam--and by the third time he will have blocked the first punch!"

Just months later, a second distributor gave the three-year-old Supercop another maior U.S. release and Chan did the publicity rounds all over again. On MTV's Beach Party, he coached Jenny McCarthy in kick-boxing and promised to star her in his next movie, and on NBC's Late Night, he staged a mock fight with Conan O'Brien, and sang-karaoke-style--the Elvis Presley chestnut, "I Can't Help Falling in Love With You!" Suddenly, the small steady Chan cult in this country bloomed to the same massive proportions found in every other part of the world. Fanatical entries could be found on the Internet newsgroups, like this one from Alt.Asian-cinema: "Jackie could kick Van Damme's ass!" New fans and old began to eagerly anticipate the steady stream of Chan flicks they will have available on the big screen instead of on grainy bootlegged videos: Thunderbolt, a wild, non-comic race-car adventure--a live Speed Racer with high-octane stunt driving; Drunken Master II, a return to the costumed kung fu genre but with Chan in some of the most amazingly choreographed fight footage ever put on film; First Strike, a globe-trotting (Russia, Australia, the Ukraine) James Bond-style adventure epic that puts GoldenEye to shame.

At 42, he expects to turn out at least one vehicle a year for the foreseeable future, before possibly working strictly behind the camera. But planning for the future is not high on his list of priorities. Nonetheless, his place in the stratosphere of all-time great film stars seems secure. But the man himself remains cheerfully down-to-earth.

"If the books of film history have all these names," he told Hong Kong Action Films, "Charlie Chaplin, John Wayne, Steven Spielberg, and just a small footnote, Jackie Chan, then that's enough. I'm happy."

(Source : www.jackiechan.com)

|

|

|